A Libertarian Defense of Winston Churchill

80 Years Since the Defeat of the Nazis, It's Time Libertarians Recognize Churchill as a Hero For Liberty

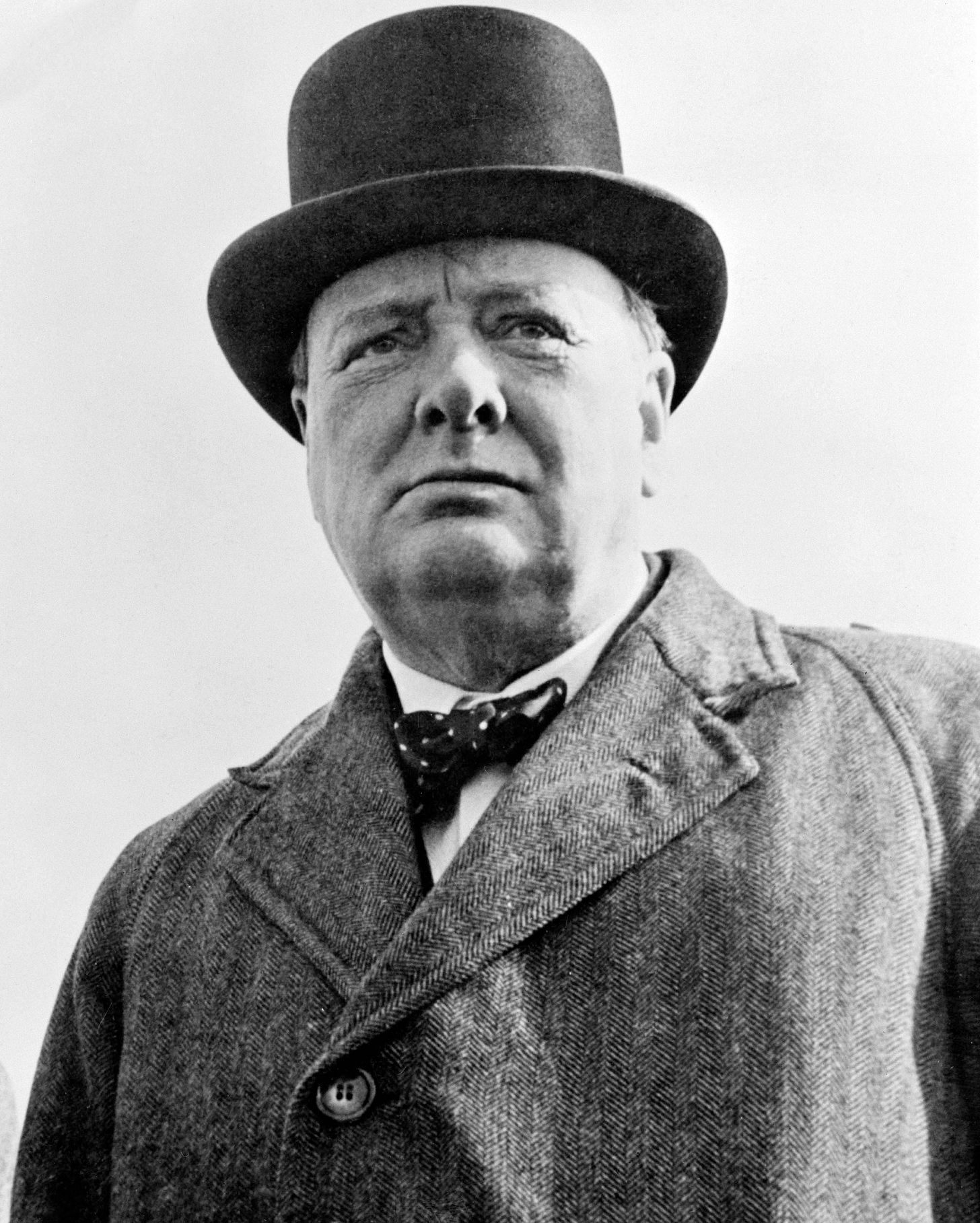

Today, May 8, 2025, marks the 80th anniversary of VE Day: the end of the Second World War in Europe. That makes it the perfect occasion to celebrate Winston Churchill as the hero for freedom that he is. More than any other single individual, Churchill was the architect of the victory which was achieved in 1945: the victory of freedom over tyranny.

On May 8, 1945, the Nazi regime was destroyed forever, and their ideology of National Socialism was banished to the political fringes where it has remained ever since. That was a real, meaningful victory for liberty and the ideals in which libertarians believe. It is preposterous to believe Churchill is a villain for having won that victory.

Yet that is precisely what some people believe. It’s understandable why Nazis and their apologists would believe Churchill is a villain–their side lost! More baffling are the libertarians who believe this. Though they have reasons which appear superficially to line up with libertarian principles, to be blunt: the anti-Churchill libertarians are not libertarians. You can’t be a libertarian and think freedom is not worth defending against tyranny.

Churchill, by contrast, believed freedom was worth defending. Indeed, freedom, he said, is what the British nation was fighting for. In his very first public speech as Prime Minister, broadcast on May 19, 1940, Churchill said “I speak to you for the first time as Prime Minister, in a solemn hour of the life of our country, of our Empire, of our Allies, and, above all, of the cause of Freedom.”

Churchill would echo that language almost exactly five years later–and exactly eighty years ago today–when a crowd gathered outside Whitehall, in London, upon hearing the news that Germany had surrendered. Churchill (apparently impromptu) addressed the crowd by saying: “God bless you all. This is your victory! It is the victory of the cause of freedom in every land.”

Throughout the war, Churchill identified his cause, and Britain’s cause, as that of freedom. Of course, Churchill had other reasons for wanting to see the Nazis defeated, not least of which was the preservation of the British Empire and security of Britain proper, but Churchill was always clear, as he was on May 8, 1945, that above all those other causes was freedom. This stood in stark contrast to the rationales offered by politicians like Neville Chamberlain or Clement Attlee, who could either not clearly elucidate why Britain was at war with Germany for a second time in twenty years or could, at best, offer up only vague platitudes.

Certainly, Churchill could be accused of using ‘freedom’ as a vague platitude, since almost all politicians invoke ‘freedom’ as their cause at some point (even Hitler did that from time to time), but Churchill’s vision of ‘freedom’ was specific, and, rooted as it was in the classical liberalism of the 19th Century, lines up neatly with libertarians’ idea of ‘freedom’ today. Churchill expounded on his vision of ‘freedom’ numerous times (mainly before or after the war rather than during it), but put it most succinctly in a private letter to his research assistant.

“The theme is emerging,” Churchill wrote on April 12, 1939, “of the growth of freedom and law, of the rights of the individual, of the subordination of the State to the fundamental and moral conceptions of an ever-comprehending community…Thus I condemn tyranny in whatever guise and from whatever quarter it presents itself.”

This is the core of libertarianism: freedom of the individual. Churchill understood then what libertarians can see clearly today with hindsight: that if the idea of individual liberty was to survive the 20th Century intact, if not unscathed, then the Nazis had to be defeated. This is not speculation or hyperbole. Not only could liberty not meaningfully exist under Nazi tyranny, but the very concept of liberty would be destroyed in the event of a Nazi victory. No less an authority figure than Adolf Hitler said so, during a speech given in Berlin on that great socialist holiday, May Day, May 1, 1939:

“And this brings up the problematic topic of liberty. Liberty? Insofar as the interests of the Volksgemeinschaft permit the exercise of liberty by the individual, he shall be granted this liberty. The liberty of the individual ends where it starts to harm the interests of the collective. In this case the liberty of the Volk takes precedence over the liberty of the individual…Above the liberty of the individual, however, there stands the liberty of our Volk. The liberty of the Reich [i.e. the state] takes precedence over both.”

This is why the Second World War has a lasting resonance to the present day; not because it is a “load bearing myth” but because it was an ideological conflict between freedom and tyranny. Freedom emerged from that conflict triumphant, and as a direct result of that conflict, freedom became and remains one of, if not the defining values of “the West” (though, admittedly, it may have been the Cold War which cemented that in place). It is no coincidence that “the Western world” and “the free world” are synonymous.

This is almost entirely because of Churchill’s wartime rhetoric, which rehabilitated the idea of freedom and attached to it the sacrifices made in the war, giving ‘freedom’ a cultural power it retains today. That is why even politicians who clearly do not believe in freedom in any meaningful sense nevertheless feel compelled to at least give it lip service in public.

For that, libertarians should recognize Churchill as the lion for liberty that he was. Though Churchill was not exactly a libertarian–he believed in a role for government–and he certainly wasn’t a saint–there is much about his conduct during the war, such as the bombing of Dresden, the suspension of habeas corpus, or the Anglo-Soviet Invasion of Iran which can be criticized fairly–it nevertheless has to be acknowledged that Churchill made the Second World War a war for freedom, and thus ensured that the post-war order would be, at least in part, founded along broadly liberal lines: free markets and free trade, limited government, and, yes, democracy (which, as Churchill himself famously said, is the worst form of government we have, except for all the others).

To be clear, the post-war period was not an immediate victory for freedom, nor yet libertarianism; Churchill was removed from power even before the war was over, in July 1945. People like Leonard Read, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Murray Rothbard, Ayn Rand, and so many other important figures of the early liberty movement, would labor for decades to rehabilitate the idea of economic freedom–a struggle which continues into the present. But the idea of political freedom, of individual liberty, had been secured. Certainly, liberty was at least saved from destruction at the hands of the Nazis.

Any who would doubt that should look to the critical months of the summer of 1940. Pardon this run-through of what is, for many, a familiar historical epic, but it’s clear that many libertarians vilify Churchill on the basis of their own ignorance. A remedial education is needed.

Churchill, of course, was not the Prime Minister of Britain when the war started; Neville Chamberlain was. It was Chamberlain who had negotiated with Hitler in the autumn of 1938: Hitler gets a slice of Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland, and, in exchange, Hitler would sign a piece of paper “symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again.”

It needs to be pointed out that Chamberlain only negotiated with Hitler because Hitler was threatening to invade Czechoslovakia and start a war, something Chamberlain hoped to avoid. Irrespective of Hitler’s motives: he was the aggressor, someone who was poised to initiate a conflict.

In March 1939, just six months later, Hitler invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia, and thus reneged on the agreement. In response to a false alarm, Chamberlain signed an agreement with Poland shortly thereafter: in the event of Poland being invaded, Britain would come to Poland’s defense (a secret clause of this agreement specified that this guarantee was good only against Germany). Churchill was not involved in any of this; he famously denounced the Munich Agreement as a total and unmitigated defeat and only approved of the guarantee to Poland after it was already a fait accompli.

When Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Britain’s government did not immediately declare war, but waited more than a day in the vain hope that war could yet be averted. Only after Britain formally joined the war, on September 3, did Churchill become part of the British government (that is: the Cabinet), however, he still was not Prime Minister.

Under Hitler’s orders, the German army had invaded and taken over Denmark and Norway in April 1940; on May 10, Churchill became Prime Minister. That same day, the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. The British army was defeated in battle, forced to retreat, surrounded, and then miraculously evacuated from Dunkirk at the beginning of June. The French surrendered on June 22, 1940. Britain was then “alone” (though, of course, Britain could count on the support of the wider Empire, Britain was the only European nation continuing to fight against Germany). Moreover, on June 10 the Italians under Mussolini had entered the war opportunistically on the German side, expanding the war to the Mediterranean and Africa. As if that wasn’t bad enough, the Soviet Union was effectively allied with the Nazis; the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, or German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, was an alliance in all but name.

Facing off against two of the most powerful states in Europe with no allies, an army with no weapons, and seemingly no hope of winning, a lesser Prime Minister may have sued for peace. There were some voices in the British government–notably, Lord Halifax–who counseled just that. Churchill would have none of it. He saw clearly that there was nothing to do but fight on. While others eventually came around to Churchill’s position, for several critical weeks it was Churchill alone who, through sheer force of will (and some canny political maneuvering) kept Britain in the war.

This is what, to normal people, makes Churchill a hero: having the moral clarity and the courage to carry on the struggle. This is where the anti-Churchill libertarians go wrong. For one thing, their belief that Churchill somehow caused the war to happen, or that Churchill wanted the war to happen, is clearly specious. Equally absurd is their idea that Churchill was a blood-thirsty politician who prolonged a war at the cost of millions of lives. This is not what libertarians thought at the time.

None other than the great economist and libertarian philosopher Ludwig von Mises said in his 1944 tome Omnipotent Government: “The reality of Nazism faces everybody else with an alternative: they must smash Nazism or renounce their [freedom] and their very existence as human beings. If they yield, they will be slaves in a Nazi-dominated world…If they do not acquiesce in such a state of affairs, they must fight desperately until the Nazi power is completely broken. There is no escape from this alternative; no third solution is available. A negotiated peace, the outcome of a stalemate, would mean no more than a temporary armistice. The Nazis will not abandon their plans for world hegemony. They will renew their assault. Nothing can stop these wars but the decisive victory or the final defeat of Nazism.”

As costly as fighting the war was, the alternative was worse. Churchill understood that, Mises understood that, and libertarians today should understand that. There was no alternative but to fight for freedom, or die a slave. If libertarians mean it when they say “don’t tread on me,” then they should celebrate Churchill’s famous pronouncement: we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight in the hills, we shall never surrender. It’s the same thing.

There are many more arguments to be had about the moral compromises Churchill made to win that war; it’s impossible to go through them all here. One elephant in the room does need to be addressed: the wartime alliance with Stalin and the Soviet Union. Stalin, of course, was no champion of liberty, and there is no denying that this wartime alliance enabled Stalin to take over half of Europe and subjugate it to Soviet tyranny. However, it needs to be pointed out that two of the major libertarian critiques of Churchill are mutually contradictory.

On the one hand, American libertarians will criticize Churchill for “dragging” the US into the Second World War, but on the other hand, they will criticize Churchill for allying Britain with the USSR. Yet, if Churchill had actually “dragged” the US into the war in 1940 or before June 22, 1941, then the alliance with the Soviet Union would never have been necessary. By June 22, 1941, when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, Churchill had failed to drag the US into the war; the US remained officially neutral until December 11, 1941. It was only after Hitler’s declaration of war on that day–more than three full days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor–that the US declared war on Germany. That fact alone is enough to discredit the idea that Churchill (rather than Hitler and the Japanese) “dragged” the US into the Second World War.

As for the alliance with the Soviet Union: there simply was no alternative. Without British aid–food, ammunition, and other war essentials–the Soviet regime may very well have collapsed, as it had in 1917, leaving the Nazis free to turn their full fury and might against the British. Equally, the Nazis had deployed nearly 4 million soldiers to invade the Soviet Union; for the rest of the war, the majority of the German military would be tied down on the Eastern Front. By the war’s end, for every five German soldiers killed in battle, four of them had been killed fighting the Soviets.

Keeping the Soviets in the war tied down more German soldiers and thus eased the burden on the British–who were, even in 1941, fully committed to a war in Europe, the Atlantic, the Arctic, the Mediterranean, and Africa, and this would soon be expanded into the Pacific and Indian Oceans, as well as Burma, India, and Australia. With no other options, Churchill proposed an alliance with the Soviets (formalized on July 12) out of sheer practical necessity.

There was, also, another consideration. Churchill had served on the front lines of the Western Front in the First World War and had seen the carnage of that conflict firsthand. Churchill had no desire to see another generation of young British men squandered in a desperate battle of attrition. Cynical though it was, Churchill can hardly be blamed for accepting the devil’s bargain: most of the fighting and dying would be done by the Soviets, not the British, saving countless British lives.

The fate of Eastern Europe after the war was indeed tragic, but half of Europe being subjugated to tyranny is still better than all of Europe being subjugated to tyranny, as it would have been if the British had withdrawn from the war in 1940. Without Britain, there would have been no D-Day, guaranteeing that all of Europe would either have been left under Nazi tyranny, or “liberated” by the Soviet Red Army. What would have stopped the Red Army marching to the Atlantic if the British and American armies hadn’t met them at the Elbe River on May 8, 1945? And if 1945 was a partial victory for freedom, then it was made complete in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed.

The wartime alliance with the Soviet Union was a practical necessity, and Churchill was one of the first Western leaders to sound alarm bells after the war was over. On March 5, 1946, Churchill gave his famous “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri. Though lauded today, it was received coolly at the time by President Truman and others who still regarded the USSR as an ally.

Much more could be said of Churchill’s conduct of the war, but it will have to be analyzed some other time. As I’ve written elsewhere, the libertarian case against Churchill is a fraud which relies on out of context quotes and an argument which rests on the assumption that the Second World War was unjust, something no libertarian can believe. Hitler started that war to bail out his failing socialist experiment and to murder Jews, and British people were fully within their rights to resist this aggression.

Up to this point, I have not directly mentioned the Holocaust. This was deliberate. It’s notable that the anti-Churchill libertarians tend to downplay the Holocaust or even attempt to blame it on Churchill or the Allies. I think it is inarguable that the Holocaust retroactively justified the Allied war effort. However, it is also true that Britain did not enter the war to stop the Holocaust or “save the Jews.”

Intellectual honesty requires analyzing Churchill’s actions in light of that fact, and the fact that the Holocaust did not enter its deadliest phase until more than a year after Churchill became Prime Minister. However, it is equally important for Churchill’s critics to acknowledge the Holocaust and that it was the Allied war effort, led by Churchill, which put a stop to it. It’s incontrovertible that more people would have been murdered by the Nazis if they had remained in power longer, though how many is up for debate. It begs the question then: if Churchill is as evil as his critics make out, why did mass murder end when Churchill’s side won?

Much more could be said about Churchill’s conduct of the war effort, but the most important fact is: Churchill’s side won. Freedom was preserved because Churchill led an ultimately successful effort to defeat the Nazis, which culminated in their unconditional surrender 80 years ago today. Because of Churchill, the world is a freer place than it otherwise would have been, despite Churchill’s actions which compromised freedom in the short term. The victory over the Nazis was not achieved without cost, but the historical record is clear: the price of freedom, though high, is worth it. The Holocaust proves it.

It’s easy for us to say that today, far removed as we are from the din of battle. But it’s significant that Churchill, Mises, and Hayek were all combat veterans of the First World War. They knew as well as anyone the horrors of modern war; all of them believed that Britain’s war against the Nazis was fully justified.

For what it’s worth, my own grandfather thought so too. Born and raised in London in the 1920s and 30s, he served in the Royal Air Force from 1939 to 1946. He lived to the ripe old age of 96, passing away in 2017. He never doubted that his own sacrifice–years away from home in deplorable conditions and for meager pay–and the greater sacrifice of his generation–which he was lucky to come out of unscathed–had been worth it.

Earlier this year, John Allman “Paddy” Hemingway passed away (suitably for an Irishman, he died on St. Patrick’s Day). He was the last living combat pilot of the Battle of Britain, those whom Churchill memorably called “the Few” to whom so many owed so much. In April, the oldest known survivor of the Attack on Pearl Harbor, Vaughn P. Drake, passed away at the age of 106.

As we observe the 80th Anniversary of the war’s victorious end, we have to face the inevitable, yet nevertheless melancholy fact that soon there will not be any living person who fought in the Second World War.

It is no coincidence that as the war slips over the horizon of living memory, we are now seeing a resurgence in Holocaust Denial and other forms of historical “revisionism” which seeks to cast doubt on the idea that the Second World War was a just war. No libertarian can doubt that.

The Second World War was fought for freedom. It’s a damn good thing the side fighting for freedom won. Churchill, and the entire generation of brave men and women who fought in that war, are owed a debt of gratitude by we the living. Let us not squander the inheritance they have bequeathed to us.

Churchhill was probably the strongest leader of the war. Hats off on this article! Great piece. My capitalist blog: https://posocap.com Cheers!